Yes, well done you uber foxy person you, you now have an extra R1.2 million to invest. This is such a common problem, I thought we should address how to handle it. Firstly, I would like to advise against spending it all on hookers and cocaine like this overly honest guy would do. Sure it’s fun, but how much of that month will you actually remember? And after you’ve lost your job, wife and the bridge of your nose, life might just suck a little afterwards. Ideally you’ll invest your winnings, but should you do it all at once, or should you spread out putting it in investments over a year or more?

Now even though I don’t currently have R1.2m to invest, I’m as curious as you are to see where things go, mostly because of those wonderful things called Tax Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs). I was one of many people who thought these were the best things since sliced bread first reared it’s head in 1928. Yes I ranked it higher than the fridge being invented in 1942, because I had to pay taxes on my fridge.

Sadly though, the accounts first appeared in April 2015, and the market was at an almost all time high. Being a very impatient guy, I just had to start buying shares so I could get some dividends and not pay tax on them so I, along with many other members on this site, put all R30 000 into shares practically straight away. Then while all our money was tied up, we all had to sit around and watch it slowly get eroded by a rather bad year for the market, until at it’s lowest it hit R26 000 and some change. We all really wished we could buy more at a discount, but the law said no, R30k is the most you’re allowed to deposit, so we just sulked away tripping on our bottom lips. At the end of the year the markets did recover a little, but I think I ended up just under R30 000, so it was still a loss of a year, I’ve only recently recovered and moved into profit.

But now we’re in a new financial year, and able to put another R30 000 into these accounts. I was thinking of doing the exact same as last year. Put all R30k into the account and allocate it straight away. It’s known as front loading, the opposite of dollar cost averaging. Just as I was about to pull the trigger, I saw a forum message from a poster I have a lot of respect for. As he generally makes a lot of sense, when he said he was going to put his money in monthly, at R2500 a month, I thought I’d better re-consider, or at least do some more research, so on with the blog post.

Conventional wisdom says that you should invest in the market in small bites. Your financial adviser will tell you the same thing, and so will the talking heads on the finance channels. As is often the case though, conventional wisdom might not be that wise. After all, conventional wisdom once said the world was flat, that margarine was healthier than butter, and that Michael Jackson was black.

I can understand the reasoning behind dollar cost averaging: What if you put all your money into one share and it crashes the next day?

As I wrote about in “It’s all about the timing”, even if we have the single biggest drop in stock market history the day after you buy your shares, you’ll probably still end up okay, but the pro dollar cost averaging crowd would have been right, you would have been slightly better off averaging your purchases over that specific year in 1987.

But how often is that the case?

In my very first blog post here I went through the stats on how the stock market is a relentless profit machine, taking any excuse to rise, and without the ability to fail long term. There were pretty graphs with scary canyons in the middle, but the trend was undeniable to anyone, the market ALWAYS went up given enough time, so surely that would say that the odds are in favour of putting your cash to work as soon as possible.

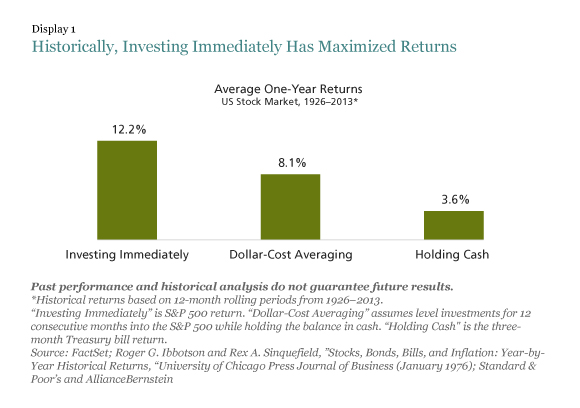

After a few days of searching I happened to find some good research from a firm called AllianceBernstein (AB, the non-super athlete AB) who went through the completely tedious but useful task of running the numbers all the way back from before the great depression up to 2013, and saved me about 3 weeks of playing with excel! They first simulated a lump sum investment in every single month from January 1926 up to December 2013, and got the totals for how well that portfolio would have done over time.

Then to get the dollar cost average numbers, they simulated 12 investments of equal value over all the 12 month rolling periods, so from January 1926 to December 1926, then from February 1926 to January 1927, carrying on all the way to December 2013. This was a huge and totally mind numbing task that only an actuary could actually find interesting, but we have to thank them for the results. What they found was the following:

To put that into plain English, on average dollar cost averaging lost out to lump sum investing by 4.1%. Now what would you rather earn on your investments, 12% per annum or 16% per annum? I’m guessing you said 16%. Of course there are always people saying that yes, on average you’re right, but what about the really bad years?

To put that into plain English, on average dollar cost averaging lost out to lump sum investing by 4.1%. Now what would you rather earn on your investments, 12% per annum or 16% per annum? I’m guessing you said 16%. Of course there are always people saying that yes, on average you’re right, but what about the really bad years?

Well AB looked at that too. They took all the years analysed and divided then into groups, the worst 25% of years, which included horror years like 1929 (The Great Depression), 1987 (Black Monday) and 2008 (The year of the idiot bankers). Then they took another group which were the best 25% of years for the US stock market, and lastly the remaining group, they imaginatively called the “Normal Years”.

There results did show one advantage to dollar cost averaging. If you can identify the 25% of really bad years for the market, you’re likely to lose 10% less by dollar cost averaging. You’ll still lose overall, but not as much as the lump summer investors. Now all you need is find a market expert to tell you when a year will be in the worst 25%. Of course after he does tell you that go and do exactly the opposite, because the odds of a market expert being right is about as large as the odds that Zuma knew nothing about Nkandla!

You should also perhaps consider the other end of the spectrum. In the 25% of the good years, you gain an extra 19.1% if you invest in a lump sum as opposed to dollar cost averaging. This is a huge chunk higher than the potential lower loss in a bad year. The risk of being wrong is nearly double the reward.

If you don’t mind those odds, then I’d like to propose we play a game. How about we have a heads or tails contest, but for money. For every time I call it right you can give me R19.10, and every time you get it right I’ll give you R10.00. I’ll play day and night with you if you like, just please make sure you bring a decent sized wad of cash! Does that sound like something you’d like to do?

Not convinced yet?

Well perhaps this study from Vanguard, the most honest investment company in the world, and also the only non-profit investment company around would help. They took two different investment amounts, $1 million, and $20 million. Around the same amount of money you find in your bank account each month for having the last name of Gupta. Then they calculated what the 10 year returns would be, starting again in every single month from January 1926 for three markets, the US, the UK and Australia.

Once they had the lump sum investment totals, they did the same thing but dollar cost averaging over different periods between 6 months and up to 3 years. The finding were clear, and in line with all other studies. On average, investing a lump sum beat dollar cost averaging 66% of the time in the US, 68% of the time in the UK and 62% of the time in Australia.

To put it bluntly, if you invest a lump sum, two thirds of the time you’ll come out ahead of a dollar cost averaged investment. Not only that, but the study also showed that the longer you took to invest the full amount, the worse your results would be on average. So a lump sum was best, and a three year dollar cost average was worst.

The conclusion from Vanguard was as follows:

Historically, a long-term upward trend has persisted for both equities and bonds, probably attributable to positive risk premia in the markets. In other words, positive returns have compensated investors for taking risks, hence the upward trend in those markets and the resulting probabilities of success for LSI. So, to the extent that an investor believes the positive risk premia are likely to exist in the future, LSI would remain the preferred method for investing an immediately available large sum of money.

That’s basically actuary speak for:

Now please excuse me while I go transfer R30k into my tax free savings account. If you haven’t done that yet I’m afraid you’ve missed a whole year, but it’s still worth doing, for yourself, your husband/wife and for your children. I can recommend ABSA Stockbrokers as being the cheapest option at just 0.20% transaction costs, with Easy Equities coming in a close second at 0.25%. I must say though, Easy Equities is far easier to deal with, and have given me great support, while ABSA Stockbrokers hasn’t answered my last three emails…

As an aside, even though I won’t DCA my tax free savings account, with my regular investment account I have no choice. Since I get paid monthly, I buy shares monthly. I’ve tried to negotiate getting a full years salary in advance, but for some reason my office wouldn’t go for that 😉